by Sharang Biswas

Cozy games are all the rage in the videogame world. Think titles like Stardew Valley and Animal Crossing, or recent indie hits such as Strange Horticulture and Tiny Bookstore. In the current, post-COVID, fascism-rising era, people seem to crave games with low stakes, gentle rhythms, and soft aesthetics. Literature, too, has witnessed a rise in the cozy genre, with books such as Legends and Lattes earning prestigious Hugo and Nebula award nominations.

Remarkably few TTRPGs spotlighting this aesthetic have achieved comparable success. Wanderhome and Brindlewood Bay come to mind, but while they both make use of cuteness and warmth as set dressings, their stakes and narrative structures prevent their reaching a truly cozy state. But perhaps the runaway success of Yazeba’s Bed and Breakfast heralds an upcoming cozy wave in TTRPGs?

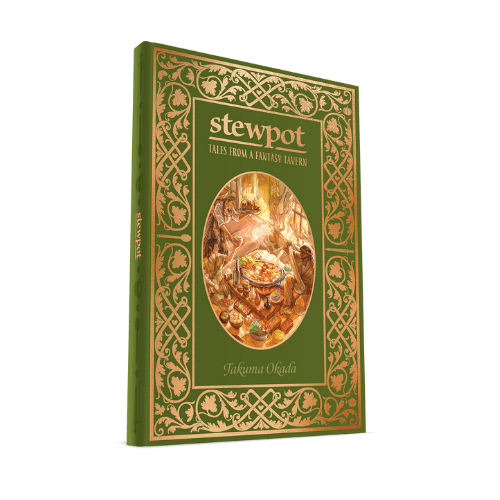

© Evil Hat Productions

If “cozy games” as a genre had a true definition, Stewpot: Tales from a Fantasy Tavern by Takuma Okada would undoubtedly fit. GMless, upbeat, and with violence existing only within memories of the past, Stewpot casts players as retired adventurers who open up a tavern, hoping to spend the rest of their lives worrying not about quests and monsters, but about the flavors of the food on offer, the quality of the service they provide to customers, and the ambience & amenities at the tavern (these three are, in fact, the only numeric stats tracked by the game). These new tavernkeeps might spend their time experimenting with new vegetable-growing techniques, helping run local festivals, welcoming distinguished guests to the tavern, or even (with a wink at those who’ve sampled the hit anime/manga Delicious in Dungeon) procuring monster parts as ingredients for experimental cuisine.

Stewpot takes a leaf out of games like The King is Dead (with its Firebrands system), and the aforementioned Yazeba’s Bed & Breakfast in that play is conducted as a series of minigames. The latter half of the book is essentially a collection of these minigames, and your group simply picks one to play through. Minigames are of varying lengths and a game session might consist of multiple; my own one-shot session consisted of eight of them, plus character creation, for four-odd hours. While a few of the minigames involve randomizers such as traditional playing cards or dice, none of them would be described as particularly “crunchy”.

For example, the minigame “Sliced” that I alluded to earlier, in which you cook up monster parts, has you draw playing cards to determine ingredient types (hearts for animal parts, spades for plants; 6 for rare creatures, 2 for poisonous ones, that sort of thing) and then roll a pair of dice for the size and habitat of the monster. After a bout of discussion, where the ingredients are further fleshed out (no pun intended), the player acting as chef rolls dice to determine how successful the dish is. What does success net you? Compliments, and the ability to add a few of your tasters as “regular patrons” to the tavern.

Most of the minigames are considerably less numbers-oriented than this, consisting of guided, back-and-forth prompts, primarily inviting freeform play. The “Wear and Tear” minigame, for instance, starts by asking the group to decide which parts of the tavern need repairs or upgrades. Then, each player gets to describe how they go about getting this work done, answering a prompt in the process. A prompt might be “You’re completely in your element. Describe how you use your experience to get the work done lightning fast,” or “You notice everyone flagging through a frustrating stretch of work. How do you lift everyone’s spirits?” Following that, players get to raise one of their tavern’s statistics, no dice-roll or card-pull needed.

© Evil Hat Productions

At the table, Stewpot thus creates a lilting, easygoing, rhythm—a rhythm that harmonizes beautifully with the game’s cozy goals. This is a departure from the rest of the cozy genre, or at least from videogames of the genre. In the videogame world, cozy games are often criticized for exhibiting coziness only at the surface level, nestling exploitative, capitalist tendencies at their heart. They tend to romanticize the running of certain types of businesses—coffeeshops, bookstores, farms—glossing over the fact they’re essentially romanticizing capitalism: monetized hygge, if you will. Samantha Trzinski writes, in the online magazine “Gamers with Glasses”:

“Both Animal Crossing: New Horizons and Stardew Valley begin with the player returning to a pastoral paradise, but it is not meant to remain in this underdeveloped way. Immediately, the player is asked to exploit this natural world: they amass natural resources by cutting down trees, mining, and foraging until the pastoral paradise is eradicated of what made it beautiful. The player constructs buildings and transforms the deserted island of Animal Crossing: New Horizons into a bustling town and the dilapidated farm of Stardew Valley into an agricultural empire. In order to “win”—or at least progress—the game, the player must devolve into the very thing that they sought to escape.”

This might be an inherent issue with videogames as a medium, though. In his talk “Videogames and the Spirit of Capitalism”, famously political game designer Paolo Pedercini contended that the digital game represents “the aesthetic form of rationalization”, the spirit of capitalism made tangible through art. He argues that “the simulated world in these games is presented as a collection of inert resources to extract. Nature is pre-quantified, subdivided into spatial units....essentiall identified by the function they perform.”

Perhaps TTRPGs, with their non-digital nature and focus on collaborative storytelling, can escape the curse Pedercini reveals, the inevitable slide into the trappings and verbs of unrelenting rationalization and optimization. But closed systems of thought like capitalism are hard to escape. Boardgames about running fantasy taverns, inns, and restaurants exist aplenty and are inevitably about making money. It isn’t a leap to imagine a TTRPG along similar lines. Dozens of blog and forum posts discuss player-run taverns (and shops) in D&D, often focusing on things like price ranges, expenses and the like.

© Evil Hat Productions

Stewpot eschews such a hard, economic approach. It tries to focus on narrative moments—both the triumphs and struggles—of newcomers trying to make it in a community. There is no money tracked, no talk of prices or profits. Your tavern has three numerical statistics yes, but maximizing them never really feels like the goal. The game doesn’t end when a certain money or advancement milestone is reached; rather, the final minigame “In the Rhythm of Things” is played when all characters have acquired a certain number of experiences in town, emphasizing the tavern’s role as a social milieu rather than an economic one. And even then the narrative doesn’t really end, per se. As the minigame’s title suggests, long after the game is over, your new tavern continues pulsing with a gentle, rhythmic life in some psychic, narrative elsewhere. The final prompt in the whole game might be emblematic of the mood it’s attempting to achieve: “What do you look forward to every week?”

Some critics note that cozy games often ignore the difficult realities that come with, say, running a quasi-medieval business, and that this aspect can be problematic. I recently watched the old BBC TV show “Tales from the Green Valley”, where a group of modern British historians have to live like medieval peasants for a year. I was reminded that rural medieval life was hard. Owning and running a tavern without starving or over-exhausting oneself would’ve required significant capital and privilege, privilege not extended to, say, religious or ethnic minorities.

In his blog, game designer Eric Merz notes that cozy games seem to avoid anything that would seem uncomfortable to the powerful:

“If you combine the general lack of ideological guidance, the emphasis on keeping discomfort away from the players and their overreliance on using predominantly white, liberal suburban aesthetics as markers for “cozyness”, you can quickly see how this could get very bad, very quickly.”

Merz is wary about games that are “more interested in shoving existing conflicts to the side, in favor of some nondescript feeling of comfort.” Characters in Stewpot are, after all, former adventurers. If they are former D&D adventurers, who knows how many murders, how much theft, how much inadvertent colonialism they were responsible for before having the privilege of spending their loot (where did the loot come from?) on running away from their pasts via a cozy business.

© Evil Hat Productions

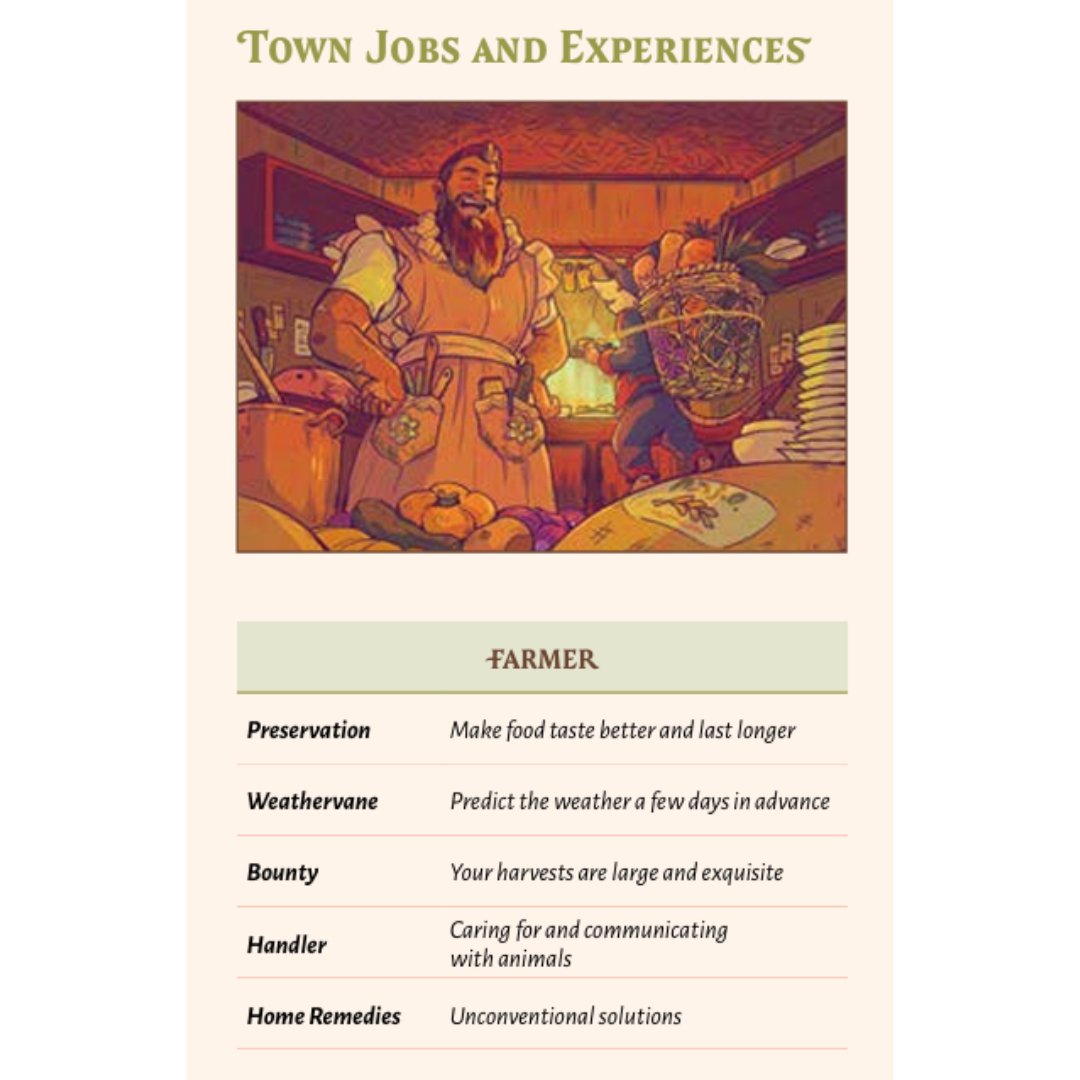

Except that Stewpot isn’t entirely about that. Stewpot characters aren’t just forgetting their histories and ignoring their privilege. In fact, if a group decides it, Stewpot can absolutely be a game about healing from trauma by forming community bonds. At character creation, players arm themselves with “adventure experiences” that stand salient from their past lives. While the book's examples all lie within the swashbuckling vein of “mastery of flame” or “extraordinary agility”, it is easy to instead imagine experiences more along the lines of “a scar that never healed” or “ghosts of the past” (two examples I just made up). To reach the final “In the Rhythm of Things” minigame, you don’t just need to add new Town Experiences, you need to replace your Adventure Experiences with Town Experiences, essentially healing from your past and looking towards a brighter, softer, more communal future.

Various minigames directly address this theme. The minigame “A Fleeting Moment” begins by asking, “What do you still carry from your old life?” and ends with having you decide whether or not to hold on to that memory. The minigame “Shields and Skillets” states that enchantments on magical weaponry tend to sour after a few years, turning your most powerful boons into literal curses. You have to hire help to strip your equipment of old magic—old lives, old selves.

Here though, we reach my main criticism of the game. While Stewpot definitely contains its share of formal flaws—confusing instructions from time to time, prompts that occasionally fail to inspire, vagueness in certain minigames, even some odd layout decisions—these missteps are forgivable given the freeform nature of the game. The greater issue is that Stewpot’s conceptual core…is ultimately a little hazy. The game feels like it’s stretching towards an argument without quite making it—a continuous, asymptomatic attempt at lucid rhetoric. There’s a half-baked, never-fully-utilized system of accruing Keepsakes that awkwardly sits at the edge of a “hoarding capital” and “cherishing mementos”. It barely came up in my playthrough. Then, if the aim is to create feelings of fellowship and community, the mechanic for adding new NPC friends to the Tavern sheet could have used more development. After all, communities are about the people within, and a sharper emphasis on that would have helped the game. Finally, Stewpot seems to want its “jobs” subsystem to pulse as an emotional core…but without clearer opportunities to actually engage with the mechanic, it falls a little flat. At times, the game feels a bit like a mishmash of “cozy vibes”.

But perhaps that’s okay. Perhaps resisting an ordered logic designed to convey specific meaning is part of Stewpot’s anticapitalist charm, resisting Pedercini’s “aesthetics of rationalization” not with razor-sharp procedural rhetorics, but with gentle, goal-less (and maybe guile-less) freeform play. Because at the end, Stewpot: Tales from a Fantasy Tavern is charming, unfussy, and satisfying. Much like a country stew.

© Evil Hat Productions

DISCLAIMER: Sharang was a Design Consultant for BLADES IN THE DARK: DEEP CUTS and has spoken on panels hosted by Evil Hat Games

Sharang Biswas has won two IGDN awards, four Ennie Awards, an IndieCade award, and a Golden Cobra award for roleplaying games, as well as the Brave New Weird Award for fiction. He has showcased interactive works at institutions such as The Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, Pioneer Works in Brooklyn, the Toronto Reference Library, and The Museum of the Moving Image in Queens. He has worked on games such as Avatar: Legends, Pathfinder, Vampire: The Masquerade, Spire: The City Must Fall, Moonlight on Roseville Beach, Jiangshi: Blood on the Banquet Hall, and Dungeons & Dragons Live, as well as boardgames including Holi: Festival of Color, Mad Science Foundation, and Sea of Legends. His fiction and poetry has appeared in Lightspeed, Nightmare, Augur, Strange Horizons, Baffling, and more. He is the co-editor of Honey & Hot Wax: An Anthology of Erotic Art Games (Pelgrane Press) and the author of science-fiction novella The Iron Below Remembers (Neon Hemlock Press). Sharang currently teaches games at the NYU Game Center and Fordham University.

© 2025 Tabletop Bookshelf

Comments (0)

There are no comments for this article. Be the first one to leave a message!