By Meghan Ellis

The stars have grown quiet. The fission engines have cooled. The rage and death have ended.

As the last living remnant of humanity, a solitary explorer must traverse a cold and remorseless galaxy to discover why they’ve been left behind. With no help except for their ship and their smarts, cyan starlight asks players to press forward, no matter the odds.

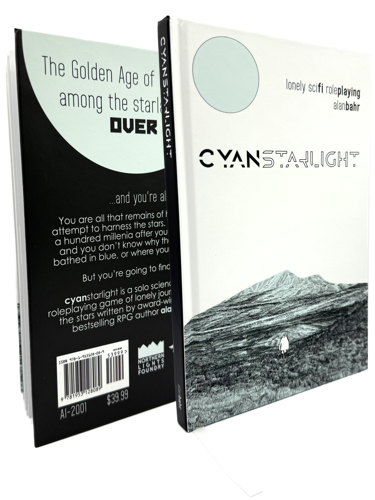

Created by Alan Bahr as a homage to the unrelenting science fiction of the 70s and 80s, this is a game about being alone, and being lonely. Before I get into the meat of the review I’ll mention that Bahr does provide content warnings around abandonment, trauma and potential suicide: cyan starlight explores his own feelings of crippling loneliness, so it’s important to remember that while playing. As he says, be kind to yourself.

Now, let’s go to the stars.

Lone wolf or lonely wanderer?

With this overarching theme of outsider-ness it feels best to play cyan starlight as a solo RPG. It’s the intended experience and ensures that the explorer has no backup to call upon when times get tough; there isn’t even a ship’s cat like Jones (Alien) or Spot (Star Trek: The Next Generation). I found this isolation to be a solid narrative hook, informing the scenario I developed for my character, a solo scout who had fallen into a low oxygen slumber before awakening in an empty galaxy. Interestingly the book offers a rollable table for choosing a name before the player learns anything about the world they might find themselves in, which is an unusual choice. After landing on Merritt D’Aramitz as my moniker, I’ll concede that cyan starlight knows how to lean into its classic sci-fi roots. Merritt, I decided, felt like a name for a cool old mentor character, à la Alec Guinness’ Obi-Wan Kenobi. But how does a mentor find purpose with nobody to guide?

In a few short paragraphs the game details the player’s goal, which is to fight against their fate and find out what happened to humanity. There’s not a huge amount of detail, but the space left between the lines allows for a unique kind of journaling experience, whether it be a captain’s log, a series of diary entries, or simple notes to be left behind as a memory.

I choose to create short scouting reports, which wove together the results from the exploratory rollable tables with a note from Merritt on his gut feeling about each new planet. The beauty of a journaling game is this ability to play in a way that interests you, though beginners to the genre might appreciate a bit more guidance to get started. Publishers Adept Icarus have a few actual play videos with Bahr to guide newcomers through the journey.

Feeling blue

Perhaps the strongest piece of worldbuilding in cyan starlight is the titular blue-green light that’s taken over the galaxy. Players will ask themselves what changed the light of space to be this colour, and depending on the ending they come to, that question may or may not be answered.

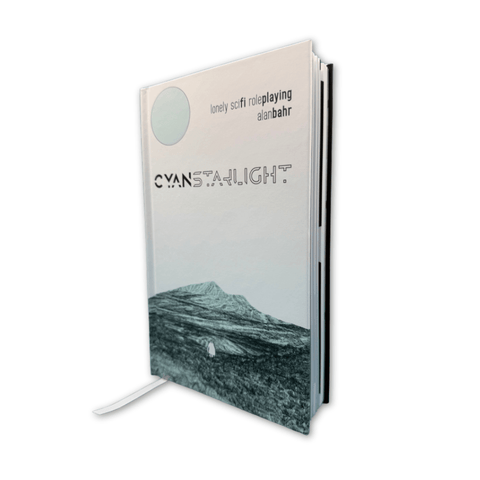

This is nicely mirrored in the presentation itself; the only color used in the book is a pale and threatening cyan, functioning as an accent colour inside and on Kattapulka’s spectacular cover art. The accompanying digital package includes access to tools to help play the game along with secrets and other additions, all presented in this same black and cyan style.

Don’t worry: none of the tools are necessary for play, but they do develop the atmosphere further. This is the first TTRPG outside of Mörk Borg where I’ve encountered a soundtrack, and while some might not enjoy integrating technology into an analogue space, I personally loved what the music brought to my time with cyan starlight. The tracks are moody and threatening and have the same cold energy as this cyan space itself

Overall, the idea of a monochrome universe was so compelling that I ended up playing with blue dice, a blue pencil, and harsh blue lighting overhead, all of which I highly recommend for setting the scene.

The last human, lost

Style like this is deeply important for distinguishing a TTRPG, and cyan starlight knows its vibe and sticks to it, unashamedly. Especially when using an existing framework - the rules here are based on the Breathless system by Fari RPGs - a game needs to have a strong visual and narrative aesthetic to set itself apart from others using the same ruleset. I’m glad that cyan starlight is upfront about its aura of bleakness, because while I found the core gameplay loop easy to understand in theory, it was difficult to actually put into practice.

Each stage of the exploration protocol - that’s flight, scan, disembark, and planetside - is done by making multiple checks balanced against a degrading set of skills for both player and ship. Narratively, this plays out as flying to a new location, scanning the surroundings and then deciding whether to disembark or move on. If the player disembarks, they move to the planetside stage. If they choose not to, then they’ll roll again on the flight table to go to a new location.

Speaking of skills, there are twelve split equally between the character and ship. During character creation the player chooses a work history and a ship model which determines their proficiency with these skills; for instance, my scout was accomplished at sneaking, which gave them a d10 to use on sneak checks. Sometimes checks are narrated to the player, and at other times it’s a personal decision on what to use and when. Unless stated otherwise a result of 1-2 is a failure with a complication and a cost, a 3-4 is a partial success with a cost, and 5+ is a success.

This might sound easy, but there are a lot of rollable tables involved in each protocol stage and its results, and it’s an endeavour to work out what rolls to make and when. Make use of the bookmark ribbon: it’ll be essential for marking where the tables section of the book begins. The book’s layout takes some time to get to grips with, and for the first few loops I was completely lost. To illustrate, in the process of deciding to disembark, a series of bad rolls might result in skill degradation, complications, loss of resources and accumulation of stress. These tables require a lot of flipping about, and they very frequently reference one another.

Bear in mind this all happens before the explorer encounters an occupying force, most of whom are generally very hostile. In cyan starlight things go wrong, fast.

Unfriendly encounters of the third kind

Forget holding out an olive branch: it’s highly likely the player will run into combat, where they can make use of any items found alongside their skills. There are tables which dictate enemy actions based on health levels, and it’s up to the player to try and outsmart or outgun the opposition. Merritt had a CamoSuit thanks to his scouting work history, which saw heavy use in a pirate encounter until I used it too many times and it broke in action.

Oh, yes: items can break, and skills degrade with use. Survival is tough. That’s the other core gameplay feature of cyan starlight: skills and items gradually get worse with each time they’re used. My CamoSuit started as a d10 item, and with each use it stepped down a dice level until it hit a d4. Because it couldn’t go any lower, (and because any roll below a 5 comes with a guaranteed cost) I narrated that the camo function failed, exposing Merritt to scattergun-shaped danger.

A tragic end for my scout, but one that felt appropriately old-school science fiction. Beware the old man in a profession where men die young, until he gets his cool death scene.

An unforgiving reality

So it’s bleak, it’s beautiful, it’s all about loneliness. The last thing I want to highlight about cyan starlight is that it’s the kind of game where it’s better to abandon the concept of ‘winning’. For example: if, like me, the player chooses a ship model with a d6 engine score, they’ll soon find this reduced to a d4, meaning it’s impossible to pass that first flight stage (remember, a pass is a score of 5+) without running into problems. Oh, and there’s no way to repair the ship.

This means limping into fights with high stress and few resources, a scenario which can very easily (and in my case did) lead to a tragic, unfulfilled end.

If this sounds overwhelming it’s because that’s the point. It becomes clear pretty quickly that this is one of the things that cyan starlight wants to explore. The game is oppressive. It’s a race against time, before the explorer succumbs to the despair of being left alone in an unfriendly world. Why should the universe wait on the whims of one person? Bahr’s exploration of loneliness and other-ness is translated into playable form through this tense and unfair gameplay. It’s bold precisely because it runs the risk of being unfun.

Don’t expect to win. Expect to get a story.

Keeping its core themes in mind, it’s no surprise that this is an unfriendly, unrelenting experience. But for players looking to experience a desperate race against the inevitable, I found it scratched the same itch as Ringworld, or the works of Robin Hobb.

Play cyan starlight to feel its ominous, monochrome despair, then crack out a cozy game for an evening chaser. Just remember to switch off its haunting soundtrack, first.

Meghan Ellis is a Glasgow-based journalist covering internet culture, anime, gaming, and SFF. She’s written for places like IGN, Kotaku and The Guardian and has appeared on the BBC, where she spoke about everything from Comic-Con to relaxing with videogames. She participates in game jams over on meghan0n.itch.io as a jack-of-all-trades artist and writer. Read more of her work at meghanon.co.uk.

Comments (0)

There are no comments for this article. Be the first one to leave a message!