by Mark Wallace

I'm a sucker for strange new worlds. Give me a place that isn't, a place that couldn't exist — especially if it's near enough to our world that you could squint and glimpse it — and I immediately start booking tickets. It's best if the world is just slightly corkscrewed from our own, twisted just enough, a place where one or two things slipped sideways at some point and the velocity of change simply carried things forward from there, far enough to make them noticeably different but still recognizable, just.

In The Wildsea, writer and designer Felix Isaacs gives us a world that beckons in just this way. It's 300 years after a world-changing event known as the Verdancy, which, in just a few days, covered the entire globe with forest, including "mile-high trees whose roots churn entire civilizations to mulch." It's these treetops which constitute the rustling waves of the wildsea, and which are sailed by the ships of the wildsailors or traversed by wavewalkers nimbly threading their way from branch to branch.

This core idea at the heart of The Wildsea — of sailing a treetop sea, uncovering secrets as you work out the unresolved business of your past — is enough to hang any kind of game on. I'd be perfectly satisfied if The Wildsea went on to say something like, "Your stats are Wind, Branch, and Blade, and you have d6 Leaves that you shed as you are injured. A leviathan ate your mother when you were a child and now you want revenge. What do you do?" But this game is nowhere near the OSR, and that is both its virtue and its most daunting aspect.

A Handsome Growth

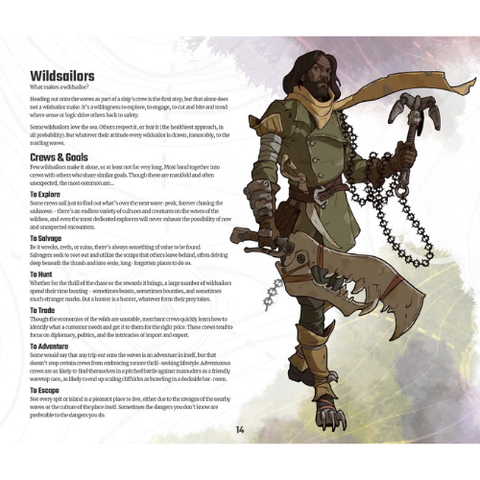

The Wildsea is a beautiful, chunky book, clocking in at over 360 pages of heavy, glossy paper in a distinctive trim size (a landscaped 8-1/2 x 9-3/4 inches), with beautiful illustrations on almost every spread (most of them by character artist Omercan Cirit and ship and environment artist Pierre Demet). And — rare for a game book — the marginal fictions that show up throughout are actually really well written. (The game won a silver Ennie in 2023 for Best Writing.) Even if you never get around to learning enough of the many rules to play the game, you'd be happy just to own the object that is this book, and browse the world that comes to life in its pages.

One of the things that makes The Wildsea a pleasure just to read is that so much of the content is so particular to the very original setting Isaacs has crafted. There are giant moss-covered pangolin, a miles-long tortoise with something like a football stadium dome for a shell, horribly mutated manticrows, an appendix of phonemes for five different languages, and treetop-sailing ships that might resemble giant chainsaws or look like something cobbled together from enormous scraps of burlwood, leviathan bones, tattered canvas, and the patched-together scraps of a long-dead civilization's long-dead machines. (I'm looking at you, page 175; literally.)

There are also no less than 17 posts (the word The Wildsea uses for classes or careers), most of which are deeply rooted in the needs of a world blanketed with overpoweringly gigantic trees. The Hacker, for instance, is skilled at hewing their way through the dense branches of the wildsea; the Navigator can plot a course through the ever-shifting branches and other growth; the Screw can meld, shape, and direct metal salvaged from wrecks and pre-Verdancy machines; and the Horizoneer is nothing less than the Indiana Jones of the treetops, "blending the disciplines of explorer and scholar... silver-tongued travellers able to charm hearts and waves alike."

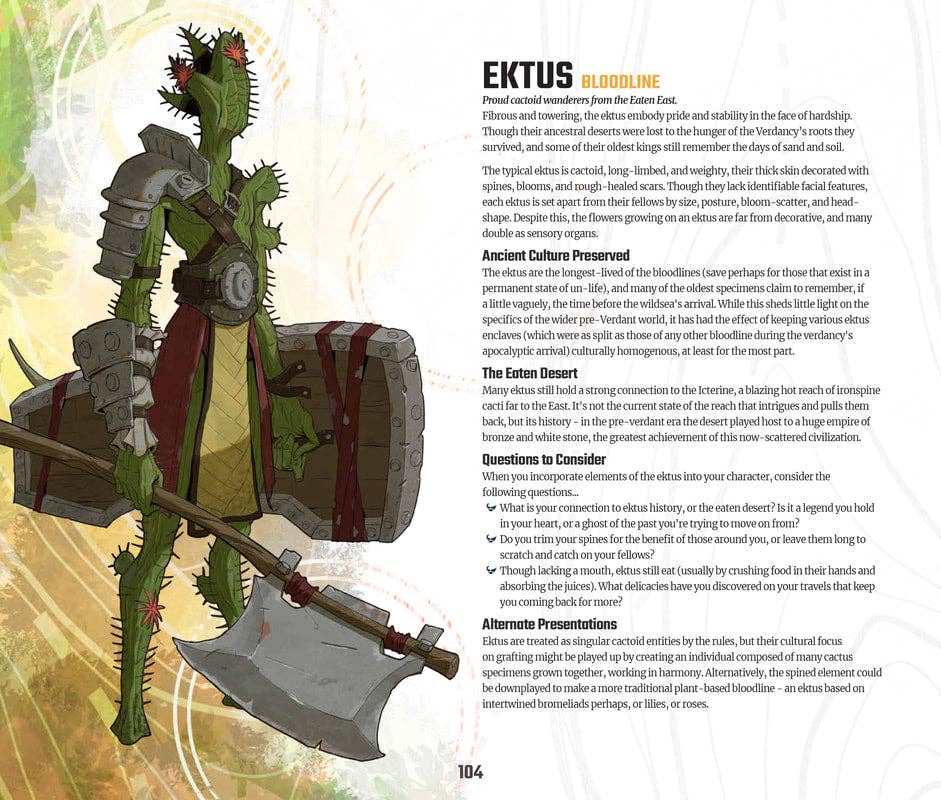

And that's not to mention the cactus people, mushroom people, people made from old ship parts, and those made from swarms of spiders wrapped in "humanesque skins" like a stack of kids in a trench coat — and those are all playable bloodlines (the word The Wildsea uses in place of the more common TTRPG trope of race).

A Mechanic By Any Other Name

By now, you may have noticed the words. Posts and bloodlines are just the beginning. To create a character, you also have to grapple with origins, edges, skills, languages, salvage, specimens, whispers, charts, drives, mires, and (I think?) more. Plus, if you're the GM — I mean, the firefly — you'll have to know about focus, tracks, twist, cut, impact, milestones... the list goes on. Not all these things are so complexly interlinked that they can't be understood more or less separately, but there are a lot of them, so that understanding them at all can feel like a daunting process.

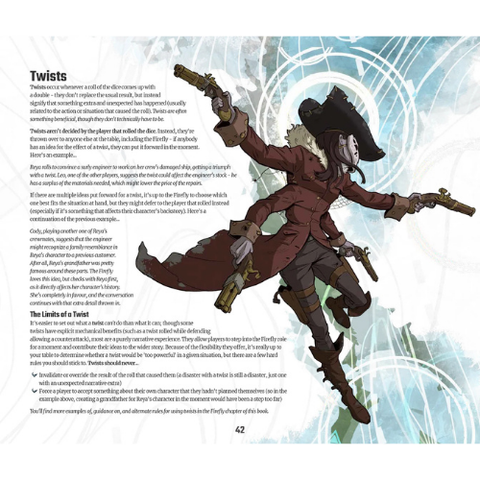

Happily, The Wildsea rests all this on a fairly solid foundation, what Isaacs calls the Wild Words Engine. The resolution mechanic at its core asks you to roll a pool of up to six d6 from a relevant Edge, a relevant Skill or Language, and any other advantages like equipment, environmental positioning, helpful crewmates, etc. A 6 gives you a success, 4-5 a "conflict" (usually a resource cost of some kind), and 1-3 a disaster (not just a failure). Doubles give you a "twist," or narrative complication that could be good or bad. It's a nice, solid system, easy to pick up. The conflict result engages the system's other mechanics well, through the various resource costs the firefly can give out, and the promotion of failure to outright disaster is a nice touch that should help the firefly envision something more interesting than an unsuccessful attempt at a task.

Unambiguous Clarity

There are a lot of small touches like this to the book, little things that help player and firefly alike to navigate the rules and the narrative of the game. In fact, there might be too many. At times when reading The Wildsea, it felt like every single little aspect of not just the game but the playing of it was mechanized into submission, as though the game doesn't quite trust its players but instead aspires to a kind of unambiguous clarity that puts the burden of rulings on the pages of the book rather than the people at the table. As mentioned above: an OSR this is not.

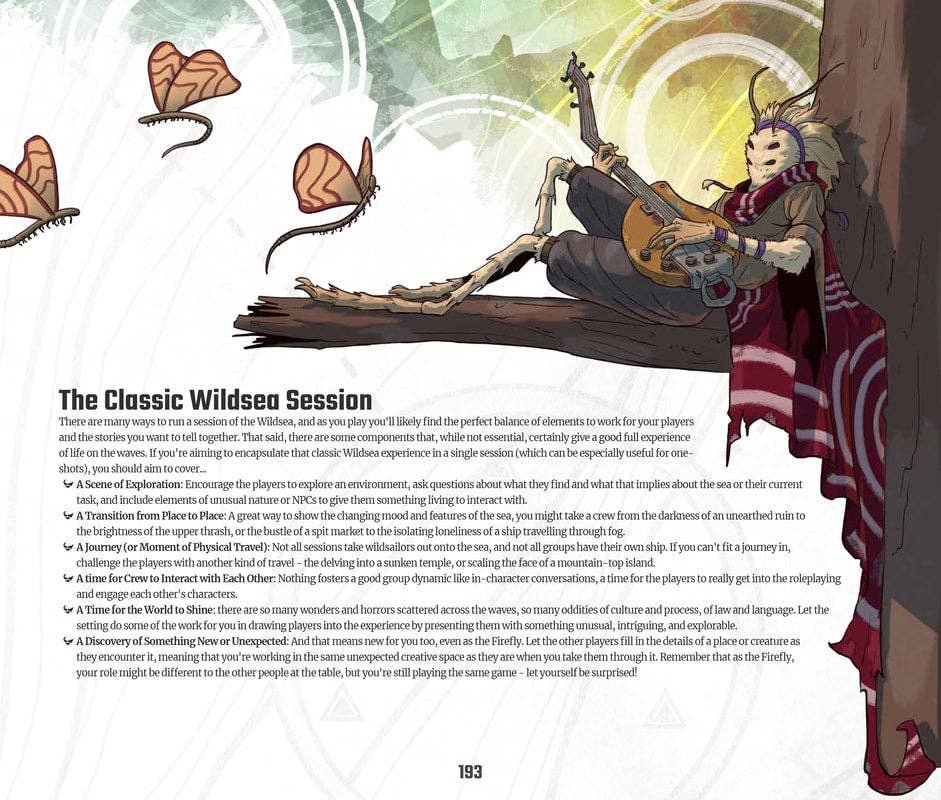

That's not a complaint, just an observation. This is not a game you just pick up and run, but one you need to sit with for a while and assess as to which of these many rules and regulations you can gloss over while you and your friends are still learning where your creativity fits in. Happily, again, The Wildsea doesn't want you on a railroad. Nestled in the various levels of the sea — the Thrash and the Tangle are where you'll spend most of your time — are Reaches: adventuring regions with their own particular flavors and factions and threats. They are situations, not stories, and it's actually here — in the places where the game lets its ambiguity sprout leaves and flowers and thorns — that The Wildsea most shines.

Long Book, Long Review

The world of The Wildsea is one that explicitly lacks magic (no surprise: too ambiguous). But the coolest things about it are the ones that are least defined. Players can obtain whispers, for instance, "living words that worm their way into an individual's mind" and can later be spoken to discover secret information, twist the narrative, or force some change in the world. They're the most ambiguous of the benefits a character can gain, and thus the most filled with tantalizing possibility. But their full description is also scattered in three disparate sections of the book, and I still can't find the place where it tells you when to hand them out, even though I know I read it the first time through.

Similarly ambiguous (complimentary) is character advancement, a rare feature of The Wildsea that has a narrative engine rather than a procedural one. Although it's also woven into a procedure, of course.

Characters get drives that can come from their bloodline, origin, or post, or can presumably be created on the fly. If your post is Slinger (as in gunslinger), for instance, you might have, "Protect the crew from boarders and pirates." If your bloodline is Ardent (the game even has its own word for human), you might have, "Make amends for an ancestor's wrongs." Make progress toward a drive and you gain a milestone (e.g., "Beat back a band of Ravenous pirates"), which you can then "consume" to do something like gain a skill rank or pick up a new aspect (the game's word for special equipment, talents, and companions). But satisfying a drive could instead give you a whisper (there it is!), and milestones can also come from narrative moments that don't necessarily speak to a drive. It's all deliciously vague, and one of the most interesting features of a game that doesn't typically leave these kinds of loose ends lying around.

Speaking of ends, it's about time this review found one. If the idea of sailing the treetops appeals to you, in one of the most fascinating settings you'll come across, pick up this game. It's worth it even just to read. I, for one, would love to visit the Thrash and Tangle. And, having spent so much time with the book, I think I'm almost ready to run the game. See you on the waves.

—

Mark Wallace (he/him) has written about games for Shut Up & Sit Down, Rock Paper Shotgun, and The Escapist, as well as for hobbyist publications like The New York Times, GQ, Wired, and many more. Find him on Bluesky at @markwallace.bsky.social.

Comments (0)

There are no comments for this article. Be the first one to leave a message!