by Mark Wallace

It's an odd truism of tabletop roleplaying games that most don't require much actual roleplay. It's just as effective to say something like, "Rupert makes an impassioned speech and then smites the dark lord with his thrice-blessed glaive," as it is to rise from the table and actually make that speech, then grab a broom and swing it around your friend's family room. Despite the impression given by many professionally produced, narrative-heavy Actual Plays, occasional moments of in-character utterance are as much play-acting as most people will want to get into. And that's fine. In TTRPGs, the hackneyed rule of prose fiction ("show, don't tell") is best observed in the breach.

Not so with VOID 1680 AM. Here is a game you can't play without being in character — despite the fact that you play it alone. And because of the particular alchemy of music, memory, and creative prompts, the character you may wind up exploring most is... yourself.

Queued Up

VOID 1680 AM is a radio game. You play as the DJ of a small AM radio station, an affiliate of parent station VOID 1680 AM. You decide your show's theme, location, time-slot, and call sign (WALC, in my case). None of these things need figure in your broadcast, but they're a clever way to get you to think about your DJ backstory. "Consider what these circumstances (and how you got to them) say about you, your choices, your motivations, and your potential audience," the game asks of us. They're a clever way, in other words, to get you to think about your life.

The mechanics are simple, and involve only a standard deck of playing cards and a single six-sided die, as well as something to play music on — and a voice recorder. For each of four song blocks, you pull three cards that give you prompts for choosing songs, then roll a die to determine who calls in while the songs are playing, and pull another card to get a prompt for what they call to talk about.

What's special about this game, though, is not how it guides you through creating the playlists and callers for each block of songs, but how you create the broadcast itself. Once you've queued up three songs for a block, you hit record, let the audience know who you are and what your show is about, and then introduce the first song — and suddenly things are on a different footing, because you can't just narrate your way through those first brief moments "on the air." It's not enough to say, "Rupert gives the station's call sign and tells his audience the theme of his show." You have to step into the shoes of your inner DJ and — with the voice recorder running — actually play the role.

Air Time

A lot of what VOID 1680 AM is up to rests on this feeling that you're live on the air. In many ways, the game is as much LARP as it is TTRPG. The mechanics are there only to lead you to songs and spark the conversation with your caller. What helps get these things under your skin is the game's relationship to time.

After you queue up your songs and intro the block, the next thing you're asked to do is stop recording and hit play. Only then — as you spend ten minutes or so listening to the music you've just programmed — do you generate your caller, their mood, and the subject of their call, and give some thought to the conversation you're having while the music plays. Game time is real time during this segment: the songs you're pretending to play on the radio are actually playing as you play the game.

That might sound like a trivial observation, but there's something powerful about those moments. The abstraction of time in most TTRPGs often distances players from the act of playing a role. There are a few notable exceptions: Stephen Dewey's Ten Candles and, in particular, Spenser Starke's Alice is Missing come to mind. In most games, time passes as quickly or slowly as the story needs it to. In VOID 1680, on the other hand, game time passes at a steady 45 RPM — at least, while the music is playing. What gives those stretches added impact is partly that the clock is out of your control, and partly that there's not much distance between the player and the role. Both you and the DJ you're pretending to be are waiting for the segment to end. Real songs are playing while real time is passing; it makes it easier to imagine that real people might be listening, or calling in from somewhere out there in the dark.

Radio Voice

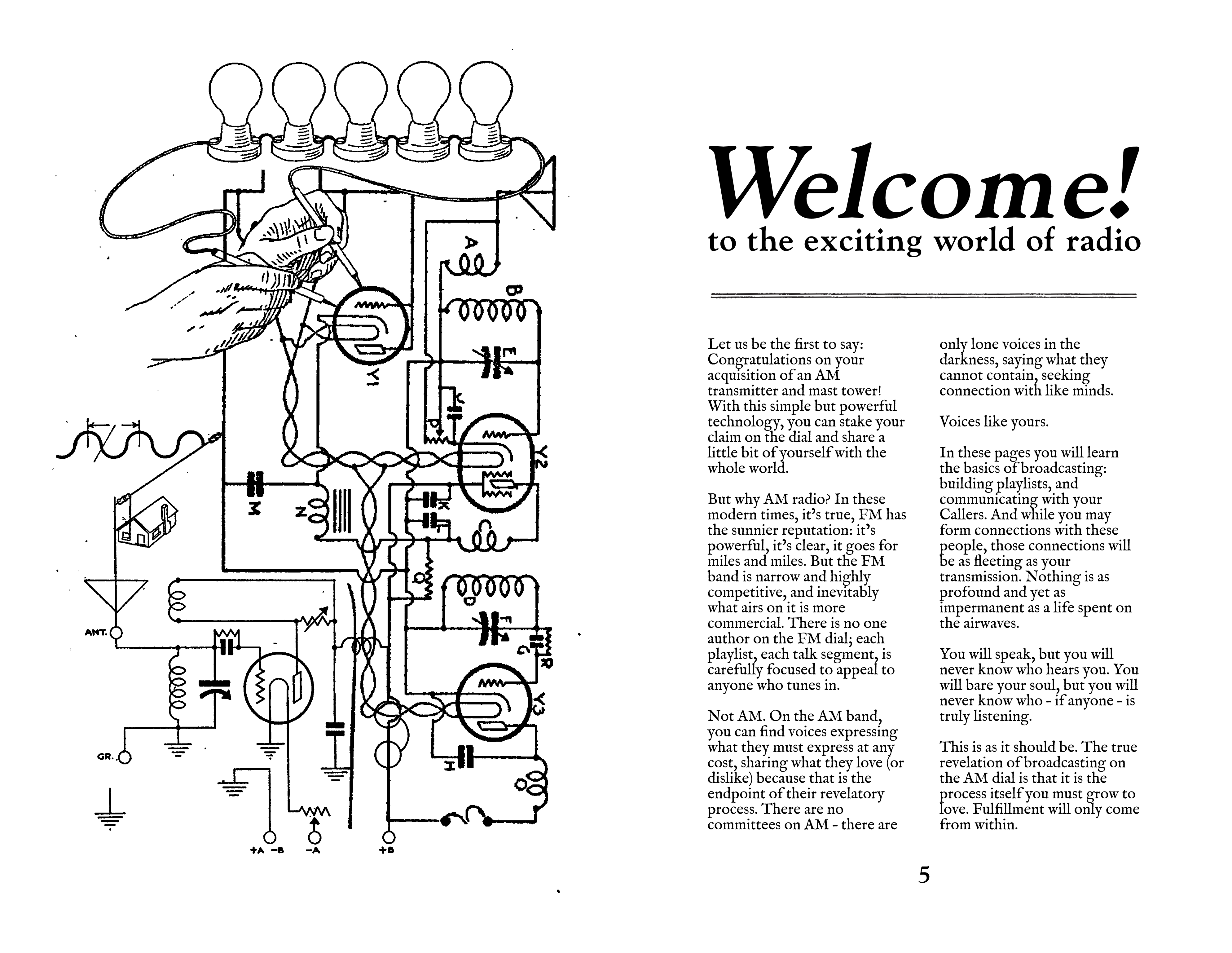

The "Owner/Operator Instruction Manual" for VOID 1680 AM clocks in at a slim 32 pages (including covers), but they're a pleasure to page through, with the clearly presented text liberally enhanced by Dylan Todd's excellent radio circuit diagrams. The book's form factor feels odd, at first — until you realize Ken Lowery, the writer and creative director who created the game, spent many years writing and self-publishing comic books; then the trim size makes a lot more sense. Lowery is also the creator of other solo games with a similarly dark and lonely feel, including the award-winning No-Tell Motel and The Lighthouse at the End of the World.

Speaking of dark and lonely, you did make your timeslot the middle of the night, didn't you? I'll admit that the temptation to play VOID 1680 as the lonely nighttime jock — that most hackneyed of radio personalities — got the better of me here at WALC. Nor could I resist slipping into radio voice when I recorded my intros and back-announced my sets. This too happens in real time — although the other impulse I couldn't resist was re-recording segments when I screwed things up, which was often. I found myself skimping on details about my callers, as well. I addressed them on air once or twice, sometimes indirectly (which is another interesting phenomenon, making an allusion that only someone who doesn't exist is going to get), but for the most part, this game for me was about the music.

The Power of Playlists

Music can be a powerful delivery vector for meaning, and science has long since established that making playlists is an intensely personal operation. Running a soundtrack behind your evening of tabletop play has become commonplace, but not many games invoke playlists as part of gameplay itself. Avery Alder's Ribbon Drive asks players to bring playlists to the table, where they become friends on a road trip listening to music that sparks ruminations about themselves, their relationships, and their pasts. Contact, by j. strautman, reimagines Samantha Leigh's excellent solo game, Anamnesis, to posit that music is how we'll communicate with aliens when they first get in touch. As in VOID (which namechecks Anamnesis as an inspiration), a playlist in Contact emerges during play, inspired by tarot draws and related prompts.

It's this emergent meaning-making that is part of what makes these games powerful. A playlist is more than the sum of its parts because it includes not just the music but the associations between the songs, their sequencing, the resonant strings they pluck within each of us. A good playlist conveys a mood; a great one tells a story. You can listen to some of the stories that come out of VOID 1680 AM on the YouTube channel where Lowery airs broadcasts sent in by VOID 1680 affiliates from around the world. Instructions for getting your broadcast on the (YouTube) air are included, as are guidelines for turning your broadcast into a continuing show.

If I were a more compact writer, I'd have space here to mention legendary DJ Vin Scelsa, and the intensely personal playlists he brought to stations around New York City for nearly 50 years, playlists that might string four different versions of the same song together, or just play the very same song twice in a row. Will your VOID 1680 AM playlists be as striking as Scelsa's? Probably not, if only because the sets are shorter. But you might find your songs and callers get under your skin the same way — striking a chord you hadn't heard in a while, or sparking a connection you'd never made before. I was occasionally taken out of the broadcast by wanting the dice to tell me more about the callers, or by wanting a more varied set of prompts for choosing songs, but those are minor quibbles. In a way, they only push the game toward realism: It's impossible to know, when you see the light flashing on the studio phone, who's calling in from the other end of your low-watt radio waves. The uncanny thing about VOID 1680 AM is that, no matter the caller, the thing you'll end up talking about is... yourself.

Mark Wallace (he/him) has written about games for Shut Up & Sit Down, Rock Paper Shotgun, and The Escapist, as well as hobbyist publications like The New York Times, GQ, Wired, and many more. Find him on Bluesky at @markwallace.bsky.social.

Comments (0)

There are no comments for this article. Be the first one to leave a message!